When You Become a Golden Retriever (or a Feral Cat)

Humanoid Robots, ChatGPT, and Why America Will Collapse if We Don't Adapt

A month ago, I published two articles on Walter Isaacson's Elon Musk biography: the first covered Elon's brutality and risk addiction, while the second examined lessons from Elon's first-principles method of solving problems. Though the bulk of Isaacson's biography concerned SpaceX, Tesla, Twitter, and Elon, there was a sidebar about Optimus, the humanoid robot that Tesla is creating for its factories. Optimus spurred my mind and inspired this post.

Today, we'll start by examining the acceleration of change and our inability to adapt well. Then we'll look at two technologies—humanoid robots and ChatGPT—that will shape the future of work faster than we realize. Last, we'll look at the dangers of maintaining the status quo of America’s safety net and consider changes we should make to the social contract.

The Great Acceleration

The landscape of work has shifted before. In one notable example, agriculture's fraction of American labor was halved between 1815 and 1900.

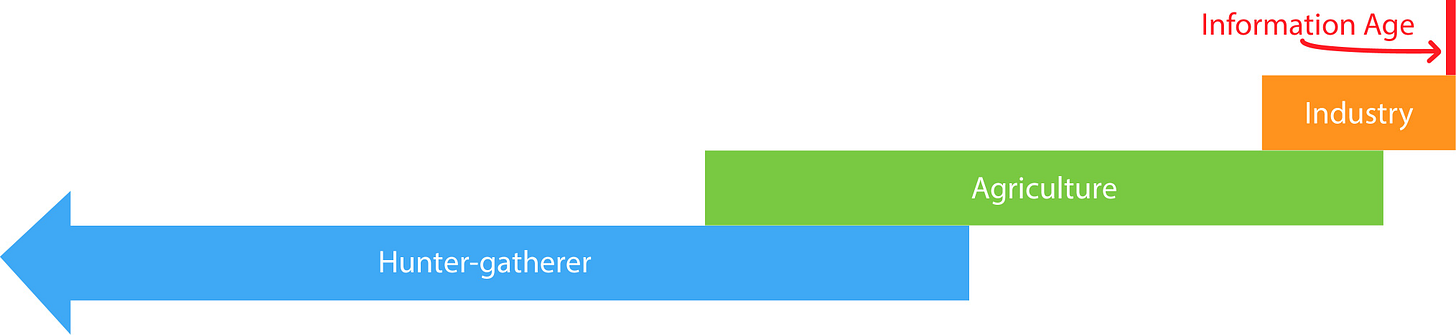

Change is precedented, but the speed of change that we will soon face in the twenty-first century job market is unprecedented. It makes sense, however, when considering history's acceleration:

At least five million years ago, the first humans emerged. For 90 percent of that time, we Homo sapiens did not exist. (The most mind-blowing fact from the book Sapiens is that several species of humans coexisted until like 40,000 years ago, including my personal favorite, the three-foot tall Homo floresiensis.)

The transition from hunting and gathering to agriculture took millennia, as the revolution occurred independently in several global regions.

The transition from agriculture to the Industrial Age took more than a century (see graph above), it and introduced us to the fossil-fuel era, which fortunately has had zero negative consequences on the planet. Like, not even one.

The transition from the Industrial Age to the Information Age has been under way for decades. It’s clearly a different era: the stock market bubbling during a global pandemic could not have happened in 1982, yet it did in 2020.

Eras Overlap Because Change Is Hard

Per the above timeline, the liminal dates of each era are not clear-cut, as evidenced by the ongoing, difficult transition from the Industrial Age to the Information Age.

As this transition unfolds and “software eats the world," we face painful friction because we're unable to simply rip up our laws and institutions and replace them with those better fit for the Information Age. (Granted, those checks and balances are a net positive overall.)

Instead of starting with a blank slate of digital-native thinking, we’ve taken the technologies of the Information Age and tacked them onto legacy institutions. I wrote about this amalgamation, called the Scanning Age, in 2021.

Just as a scan is the offspring of a physical document and a digital-native PDF, other forms of scanning exist all around us: ad-based online newspapers, centralized banking done online (complete with money orders and everyone’s favorite, the “bank wire”), and even the Zoom version of traditional school during COVID.

As we straddle the analog world and digital world in the Scanning Age, technology's attention economy has created an objectively more polarized country, and it’s regulated by the best and brightest graduates from the class of 1955.

We are not good at quickly adapting to technological change, hence the lengthy overlapping eras.

Change Accelerates

Since the rate of change accelerates and we don't adapt well to change, the next wave of change will arrive—frighteningly—long before we figure out how to resolve the current existential threats.

We can't merely try to catch up to where the world is now, because by the time we properly adapt to the Information Age, we'll be left in the dust again. We have to rapidly adapt our institutions (more on this below), laws, and ourselves to prepare for what comes next, because "what comes next" is already here.

The Next Wave is Already Here

The next-wave technologies that will reshape labor already exist—they just haven't matured yet (or as William Gibson would say, “The future is already here, it’s just not evenly distributed”). Take, for instance, ChatGPT and Optimus—Tesla's robot.

ChatGPT

OpenAI, an artificial intelligence research organization, took the world by storm in late 2022 when it released ChatGPT, its generative-AI chatbot. What makes ChatGPT revolutionary, and unlike Google Search, is its ability to create coherent text, not merely retrieve results from human-written text, websites, images, books, etc.

The creation of new content extends beyond text: OpenAI's "DALL·E" application creates images from a text prompt, song generation exists all over the internet, and the inevitable AI-generated videos are sure to wreak havoc soon.

ChatGPT's integrations with computational engines like Wolfram|Alpha are adding factual correctness to ChatGPT's human-like responses. The implications are massive, and I’m certain that these "plugins" could now do all the homework I did as a kid, convincingly, accurately, and in seconds.

And if ChatGPT can do your homework, it can do an increasing number of your work tasks, too.

Optimus

Moving from software to hardware, the capabilities of Optimus, Tesla's aforementioned humanoid robot, are already quite impressive.

Although companies like Boston Dynamics had a huge head start (and have built robots that can do cute dances and parkour), Tesla's plan of initially deploying Optimus on narrow manufacturing tasks—e.g. the Tesla factory floor—will allow it to improve quickly, expand its capabilities, and eventually leverage Tesla's massive production scale.

Tesla is already roughly a trillion-dollar company, yet Elon Musk envisions Optimus as its main driver of future profits once Tesla begins producing Optimus by the "millions.” “Robots are going to work harder than humans work,” he correctly points out.

Not only will robots work harder, you can put humanoid robots in dangerous factory situations, have them do repetitive tasks all day, give them zero vacation days, and even deprive them of health insurance.

In the long run, Optimus (and similar robots) "could transform the world as profoundly as the automobile or smartphone," writes Stephen Shankland.

The purpose of humanoid robots is to free humans from doing repetitive and dangerous tasks, those that bore us or gore us. In doing so, these robots will replace lots of jobs.

Although humanoid robots remain mere prototypes—whereas ChatGPT gained 100 million-plus users within months—the seedlings of a future with artificial general intelligence (AGI) and armies of humanoid robots are already here. As technologies like Optimus and ChatGPT mature like the internet has over the past 30 years, their effect on labor might seem as epochal as the transition from hunting to farming.

Before we examine an America in which we evolve—politically—alongside technology, let's consider what might happen over the coming decades if our current systems remain in place.

A Status-Quo Future: People as Feral Cats

Automation is not a new concept. Machines (and geographic outsourcing) replaced large swaths of American factory jobs over the past century. Fortunately, even more new jobs emerged in the aggregate.

Many people cite this "creative destruction" in order to dismiss automation concerns: If automation creates more new jobs than it destroys, why should we be concerned about a "new wave" of AI and robot automation?

This argument has a foundational truth supporting it: jobs will not vanish forever in the aggregate, because all jobs are made up.

The idea of having a "job" that we do in exchange for a wage is a story that exists entirely in our collective minds. There were no salaried employees in 30,000 B.C., no baristas in the year 1400, no software sellers in 1945, and no professional TikTokers in 2015. As soon as some jobs vanish, we make up others, and we'll do it again after the next wave of automation.

Thus, the concern shouldn't be the permanent elimination of all jobs, but rather that our country and its institutions are not remotely prepared for the pace that labor can now change.

It's a safe bet that artificial intelligence and humanoid robots will reshape or eliminate tens of millions of knowledge-work and manufacturing jobs, respectively, in the next decade or two. That elimination would lead to levels of structural unemployment that nobody alive has seen.

When owners of technology (read: capitalists with the capital) replace human labor with robots and AI, income and wealth will concentrate even more at the very top. That concentration, plus the “winner-take-all” nature of the Internet’s global marketplace, is a trend that’s already underway.

America's gap between the rich and poor is wider than that of ancient Rome (per Walter Scheidel), an empire built on slave labor.

The next chart portrays the growth of inequality, where the steepest decline has occurred in the middle class.

"Middle class" is likely to be a foreign concept to the next generation, if it still exists at all in 2023.

It seems that three career paths will be viable if the status quo remains.

The first path is to be a capitalist, an entrepreneur who reaps the rewards of ownership. Nobody who is currently an employee would fall into this category.

The second path involves hard skills that robots cannot replace any time soon, or those for which people would pay a premium to see a real person: doctors, plumbers, service workers (cooks, bartenders, restaurant staff, EMS workers, countless frontline healthcare employees, firefighters), electricians, carpenters, and so on.

The third path—surviving as a knowledge worker—will be the most frightening and unpredictable.

Though many knowledge-work jobs will be automated by AI, others will exist indefinitely because they are too contrived to be replaced. For example, as Rutger Bregman wrote in his book, Utopia for Realists, sanitation workers went on strike in New York City in 1968 and the city shut down within days. However, if all 100,000 D.C. lobbyists quit tomorrow, most Americans would not notice. AI will be able to write code better than some software engineers, but it can't wine and dine a legislator.

As AI replaces more and more of a knowledge worker's tasks, their lone salvation will be the credentials of their education. "As long as machines can't go to college, a degree offers higher returns than ever," writes Bregman.

(The best explanation I've heard for the skyrocketing cost of college is not the fancy dorms, but that schools gradually realized student demand was inelastic—that is, tuition increases didn’t affect demand. The value of a degree's credentials far exceed the value of the education itself—you can learn anything online)—so people are as willing as ever to go into decades of debt for that certificate.)

Until the importance of traditional employment declines, we'll continue propping up jobs through gatekeeping, even if millions of these jobs are increasingly BS and provide zero meaning or usefulness.

So, what happens when the millions of people who fall outside of those three job buckets become unemployed and turn towards a broken safety net?

The reactionary politics that became obvious in 2016 could worsen as inequality worsens.

Many people would dread the status quo more than they'd fear punishment, so violence and looting would increase. Few people would care to protect the property or interests of the .01 percent, so the extreme-wealth class might congregate and pay for private security instead of relying on the police, which would challenge the government's current monopoly on violence.

If that sounds to you like a return to the feudal system, you wouldn't be wrong. Fortunately, a functioning democracy—emphasis on functioning—could alter the welfare state and increase wealth redistribution before completely imploding into a feudal state or revolution. (One challenge to wealth redistribution in the current system is that hiking marginal income taxes will barely affect the top, because labor income is a minority of their wealth.)

In the long run, technology can also lower inequality—3D-printers and cheap energy could decentralize production (people are already 3D-printing guns). But technology will probably centralize power and increase inequality before it can do the opposite.

Let's get out of dystopia and transition to the only near-certainty of the post: the tectonic shifts in the labor market will arrive before most politicians decide to take notice.

The implications of purely-reactive politicians are terrifying. We don't have the systems in place to deal with mass structural unemployment or inequality that rivals the Gilded Age. To avoid that fate, we need to alter America's social contract right now. How might we do that?

A Better Future: People as Golden Retrievers

Let's examine a few ways we can build a new social contract.

Universal Basic Income (UBI)

At its simplest, a UBI pays all people a fixed sum, regardless of their wealth or employment status. It's not as radical as you'd think—Richard Nixon's (!) UBI bill got through the House of Representatives in 1970, and very nearly the Senate, too.

There are countless strong arguments both for and against UBI. I originally laid several out here, but I’d rather do a deep dive into UBI in the next Future of Tuesday.

I find the moral opposition to a UBI—"UBI breeds laziness and nobody will work"—much less compelling than the practical opposition—"How would we prevent people from just voting themselves more and more money and turning us into some broken socialist state?"

I strongly believe that 99 percent of people would not become bums if they were offered free income that marginally exceeded the poverty line. I've literally never met someone who makes $100k who would not like to make $200k. For the 1 percent of the population who wouldn't want to work, they were likely not working before—so UBI’s dramatic reduction in the waste of the current welfare system is all upside.

The bottom line is that we really don't know what kind of UBI would work best, and it's irresponsible and dangerous that we haven't recently tested UBIs at state or municipal levels (i.e. used the scientific method).

The American government does two remaining things well: it collects taxes and sends people checks. (Remember during COVID when the government magically deposited money into bank accounts?) We've thus proven that a UBI is systematically feasible, even if we don’t like its consequences.

A literal UBI might not be the answer, but then again, neither is the status quo.

Separating Healthcare from Employment

I am not here to make a dumb straw-man argument and say that socializing healthcare is a silver bullet. Patients come from single-payer states (e.g. Canada) all the time to get specialized treatment in the US. Although graphs like the following would make you think everything is broken, that's not the full story.

Across pharmaceuticals, vaccines, cancer research, and more, America subsidizes much of the world's cost of medical innovation, which bloat the cost.

Separate from that subsidizing, there remains far too much waste. Marty Makary's The Price We Pay is an excellent book about the numerous break points in the system that allow insurance companies, healthcare CEOs, brokers, and many others to line their pockets at the expense of healthcare workers and patients.

Like income, healthcare is currently tied to employment for everyone above the poverty line and under age 65. For the purposes of this post, that's what concerns me most.

Channeling health insurance through employers made sense in 1946, as I've written before, but there is a massive opportunity cost to doing so now. Countless would-be entrepreneurs are unable to take risks—i.e. quit their day jobs—solely because they need their employer's friendly health insurance plan. People who do successfully start a business are gifted the burden of supplying insurance to their own employees, which bankrupts small businesses.

Forget the chaos with health insurance if America faces mass unemployment, because the employer-funded system is killing us as we speak.

Redefining Work, Finding Meaning

"The world is not static: to replace humans is, in the long run, to free humans to create entirely new needs and means to satisfy those needs." - Ben Thompson

Naval Ravikant, Silicon Valley guru, said on a podcast in 2019, "If we were all engineers, we'd stop working within 5 years." He doesn't mean people would do nothing, but rather that people would do work of their choosing. Work provides people with meaning, but only when that work is meaningful.

The distinction between "a job" and "not a job" are increasingly arbitrary. Why is raising children or volunteering at a shelter not considered "a job," while being a phone operator or TikTok Influencer is?

People want to work (long-term unemployment has a greater impact on well-being than divorce or the loss of a loved one does), but they want to spend their time doing work that isn't pointless or miserable. Too many jobs fall into one (or both) of those categories.

"The role of humans as the most important factor of production is bound to diminish," Wassily Leontief, the Nobel laureate, wrote in 1983. Thus, in the long run, we must disentangle "having a job" from "meeting our basic needs."

As the next wave of automation swells, we have two choices. The first is to create pointless jobs for people, furthering the ongoing crisis of meaning (which my friend Cesar Garcia eloquently wrote about on his Substack).

The second is to provide a safety net that is not tied to an outdated conception of a "job." If we do that, people will pursue more meaningful work—from climate change to education to caring for aging family members—that the free market barely rewards today.

For millions, work would feel less like work and more like creative expression, sometimes even play. We would become more like golden retrievers and less like feral cats, clawing at the rich and fighting over their scraps.

Conclusion: Beyond a Moral Argument

It's in the interest of the .01 percent—those who benefit from America's increasing inequality—that we put systems in place to prevent the fracturing of society. Of what use is an extra $10 million to a billionaire if the last valuable assets are gold, guns, and canned food? I'm being dramatic, but my point is that modernizing the social safety net is more than a moral imperative—it's key to the survival of the country.

Sadly, few local governments are girding themselves for change, and many state governments would rather spend time regulating women's bodies, 50 years after Roe v. Wade. Federally, we dig deeper and deeper into debt to prolong our unsustainable status quo. I look forward to the day when a single, competitive presidential candidate acknowledges that a paradigm shift is hurtling towards us (no, Andrew Yang was not competitive).

America became the global hegemon because immigrants left the staid Old World for the land of unbounded possibility and innovation. Those immigrants and their children (and slaves, to be clear) built the world we live in by letting go of outdated institutions.

It's easy to feel constrained by the giant weight of America's past, but for our kids and grandkids to prosper, we must take a page from that past and let go of it.

I cynically abandoned politics after college, yet I've recently come to realize that technology alone cannot save us. We have to innovate, politically, and we're not doing that—Biden vs. Trump is the clearest sign that we're looking backwards for answers, not forwards.1

The path of slow decline is not inevitable.

As Alexander Hamilton wrote in the unpublished Federalist Paper 86, "From the pool of age-35-and-over Americans, voters shall decide between two white males, one of whom must have dementia, while the other must be facing felony charges for defrauding these United States. These shall be our best options."